The Basics of Waves¶

There are many types of waves in our life, for example, if you throw a rock into a pond, you can see the waves form and travel in the water. Of course, there are many more examples of waves, some of them are even difficult to see, such as such as sound waves, earthquake waves, microwaves (that we use to cook our food in the kitchen). But in physics, a wave is a disturbance that travels through space and matter with a transferring energy from one place to another. It is important to study waves in our life to understand how they form, travel and so on. In this chapter, we will cover a basic tool that help us to understand and study the waves - the Fourier Transform. But before we proceed, let's first get familiar how do we actually model the waves and study it.

Model a wave using mathematical tools¶

We can model a single wave as a field with a function $F(x, t)$, where $x$ is the location of a point in space, while $t$ is the time. One simplest case is the shape of a sine wave change over $x$.

x = np.linspace(0, 20, 201)

y = np.sin(x)

plt.figure(figsize = (6, 4))

plt.plot(x, y, 'b')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.xlabel('Location (x)')

plt.show()

We can think of the sine wave can change both in time and space. If we plot the changes at various locations, each time snapshot will be a sine wave changes with location. See the following figure with a fix point at $x=2.5$ showing as a red dot. Of course, you can see the changes over time at specific location as well, you can plot this by yourself.

plot_sine()

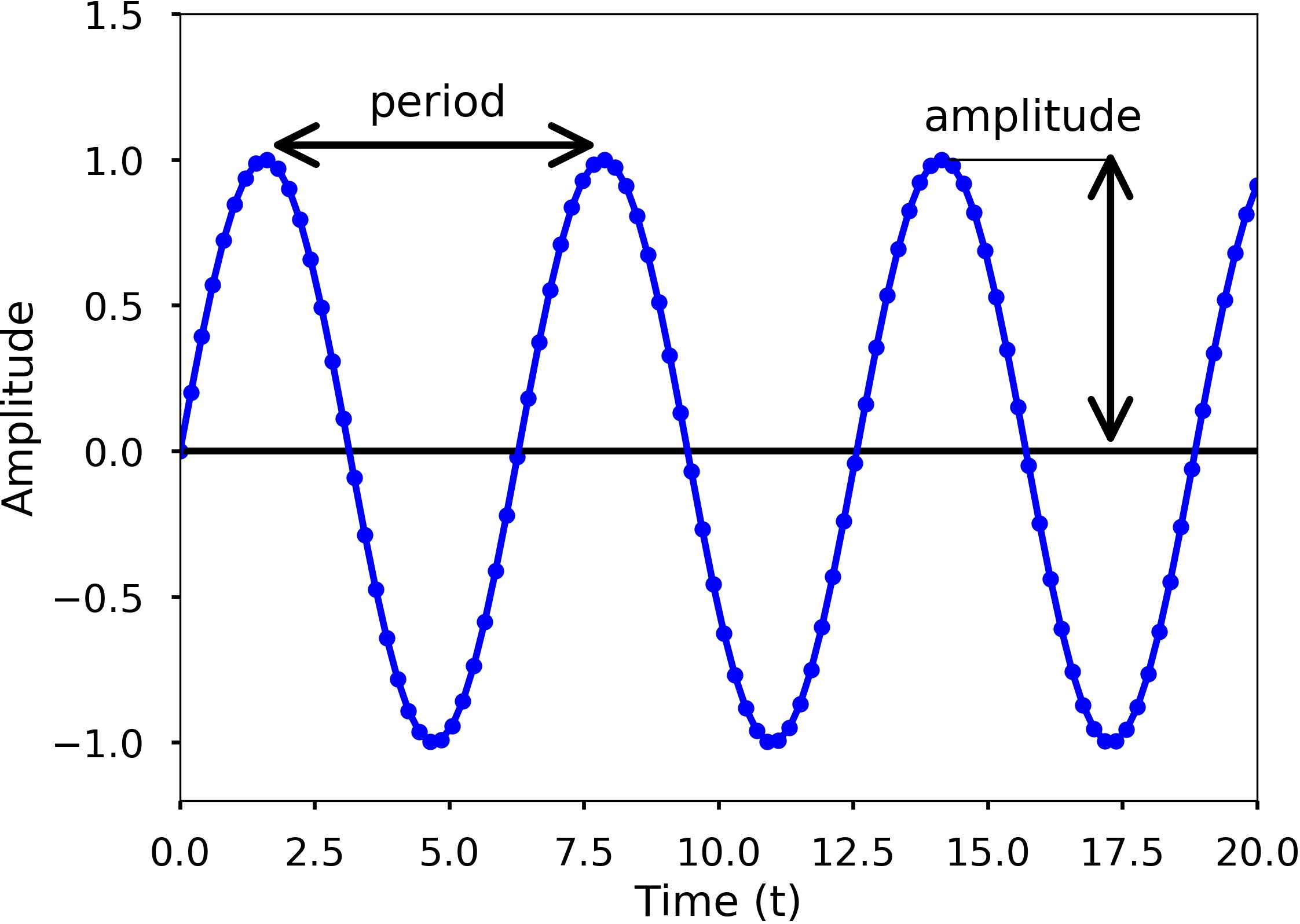

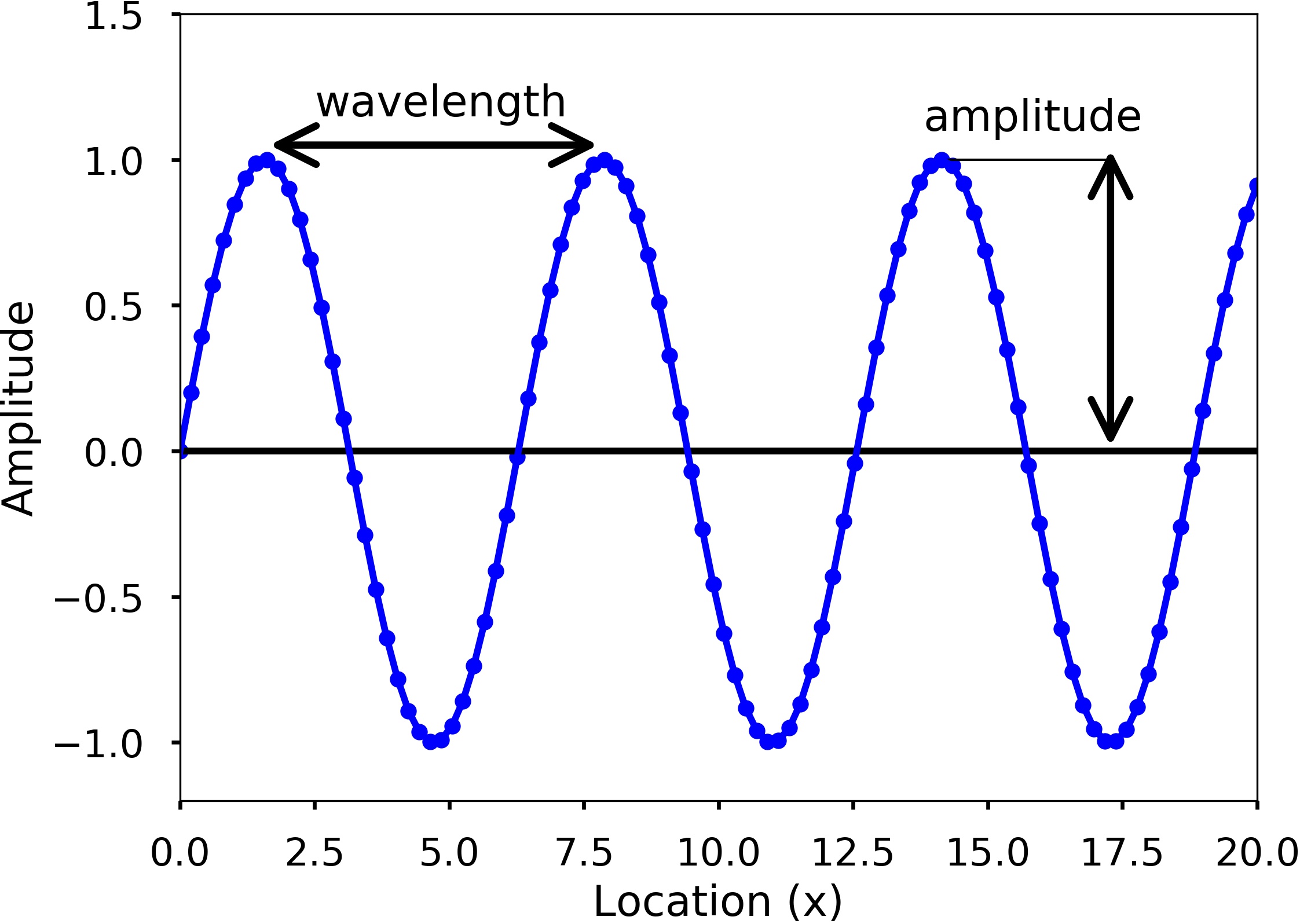

Characteristics of a wave¶

We can see waves can be a continuous entity both in time and space. But in reality, many times we discrete the time and space at various points. For example, we can use sensors such as accelerometers (can measure the acceleration of a movement) at different locations on the Earth to monitor the earthquakes, which is spatial discretization. Similarly, these sensors usually record the data at certain times which is a temporal discretization. For a single wave, it has different characteristics. See the following two figures.

Amplitude describes the difference between the maximum values to the baseline value (see the above figures). A sine wave is a periodic signal, which means it repeats itself after a certain time, which can be measured by period. Period of a wave is time it takes to finish the complete cycle, in the figure, we can see that the period can be measured from the two adjacent peaks. Wavelength measures the distance between two successive crests or troughs of a wave. Frequency describes the number of waves that pass a fixed place in a given time. Frequency can be measured by how many cycles pass within 1 second. Therefore, the unit of frequency is cycles/second, or more commonly used Hertz (abbreviated Hz). Frequency is different from period, but they are related to each other. Frequency refers to how often something happens, while period refers to the time it takes to complete something. Mathematically,

$$period = \frac{1}{frequency}$$

From the two figures, we can also see the blue dots on the sine waves; these are the discretization points we did both in time and space. Therefore, only at these dots have we sampled the value of the wave. Usually, when we record a wave, we need to specify how often we sample the wave in time, called sampling. This rate is called sampling rate, with the unit Hz. For example, if we sample a wave at 2 Hz, it means that every second, we sample two data points. Since we understand more about the basics of a wave, now let's see a sine wave more carefully. The following equation can represent a sine wave:

$$ y(t) = Asin(\omega{t}+\phi)$$

Where $A$ is the wave's amplitude, $\omega$ is the angular frequency, which specifies how many cycles occur in a second, in radians per second. $\phi$ is the phase of the signal. If $T$ is the period of the wave, and $f$ is the frequency of the wave, then $\omega$ has the following relationship to them:

$$\omega = \frac{2\pi}{T} = 2\pi{f}$$

🚀 In class¶

Generate two sine waves with time between 0 and 1 seconds and frequency is 5 Hz and 10 Hz, all sampled at 100 Hz. Plot the two waves and see the difference. Count how many cycles in the 1 second.

# sampling rate

sr = 100.0

# sampling interval

ts = 1.0/sr

t = np.arange(0,1,ts)

# frequency of the signal

freq = 5

y = np.sin(2*np.pi*freq*t)

plt.figure(figsize = (8, 8))

plt.subplot(211)

plt.plot(t, y, 'b')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

freq = 10

y = np.sin(2*np.pi*freq*t)

plt.subplot(212)

plt.plot(t, y, 'b')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.xlabel('Time (s)')

plt.show()

Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)¶

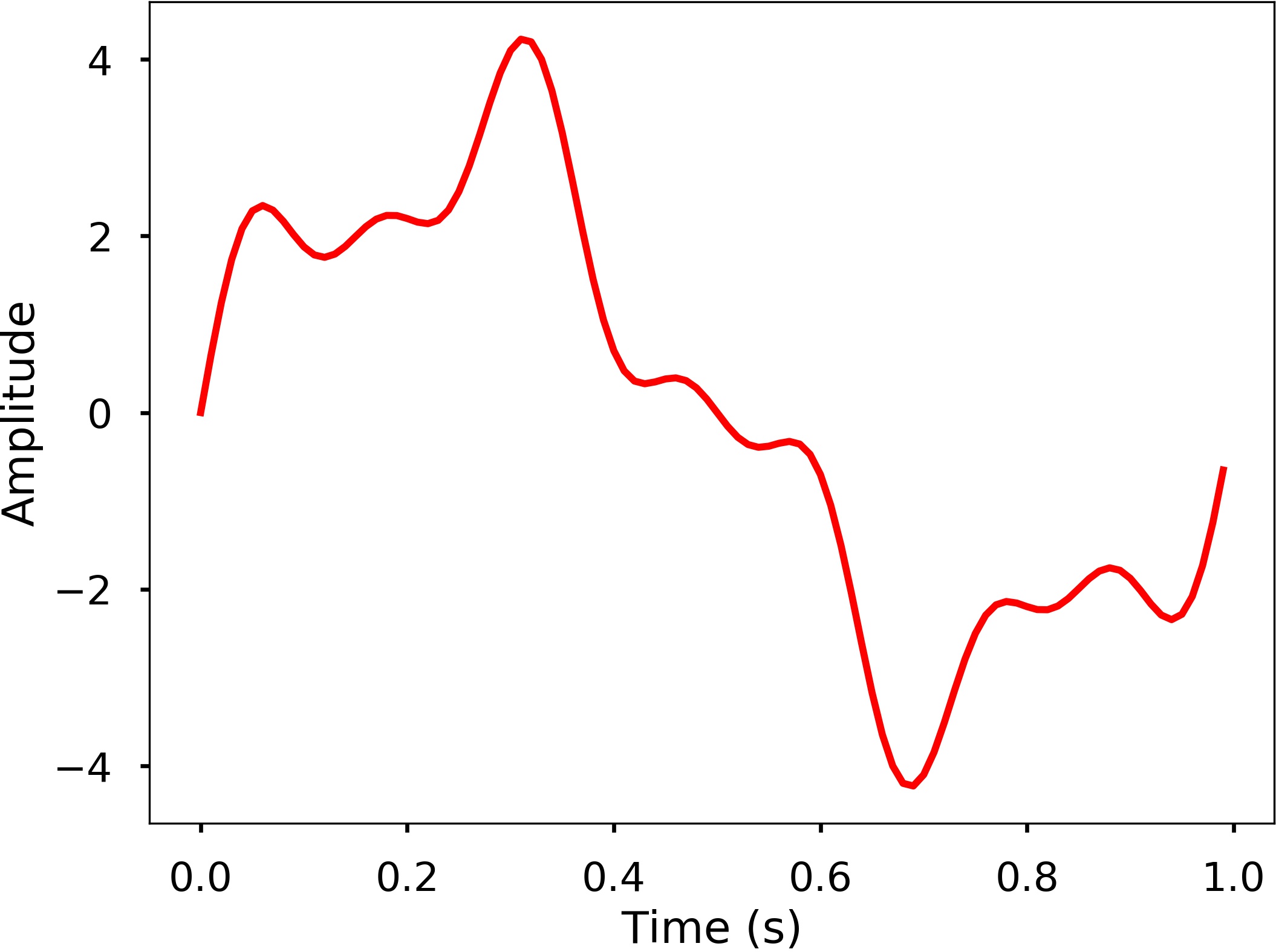

We learned how we can quickly characterize a wave with period/frequency, amplitude, and phase. But these are easy for simple periodic signals, such as sine or cosine waves. For complicated waves, it is not easy to characterize like that. For example, the following is a relatively more complicated wave, and it is hard to say what the frequency and amplitude of the wave are.

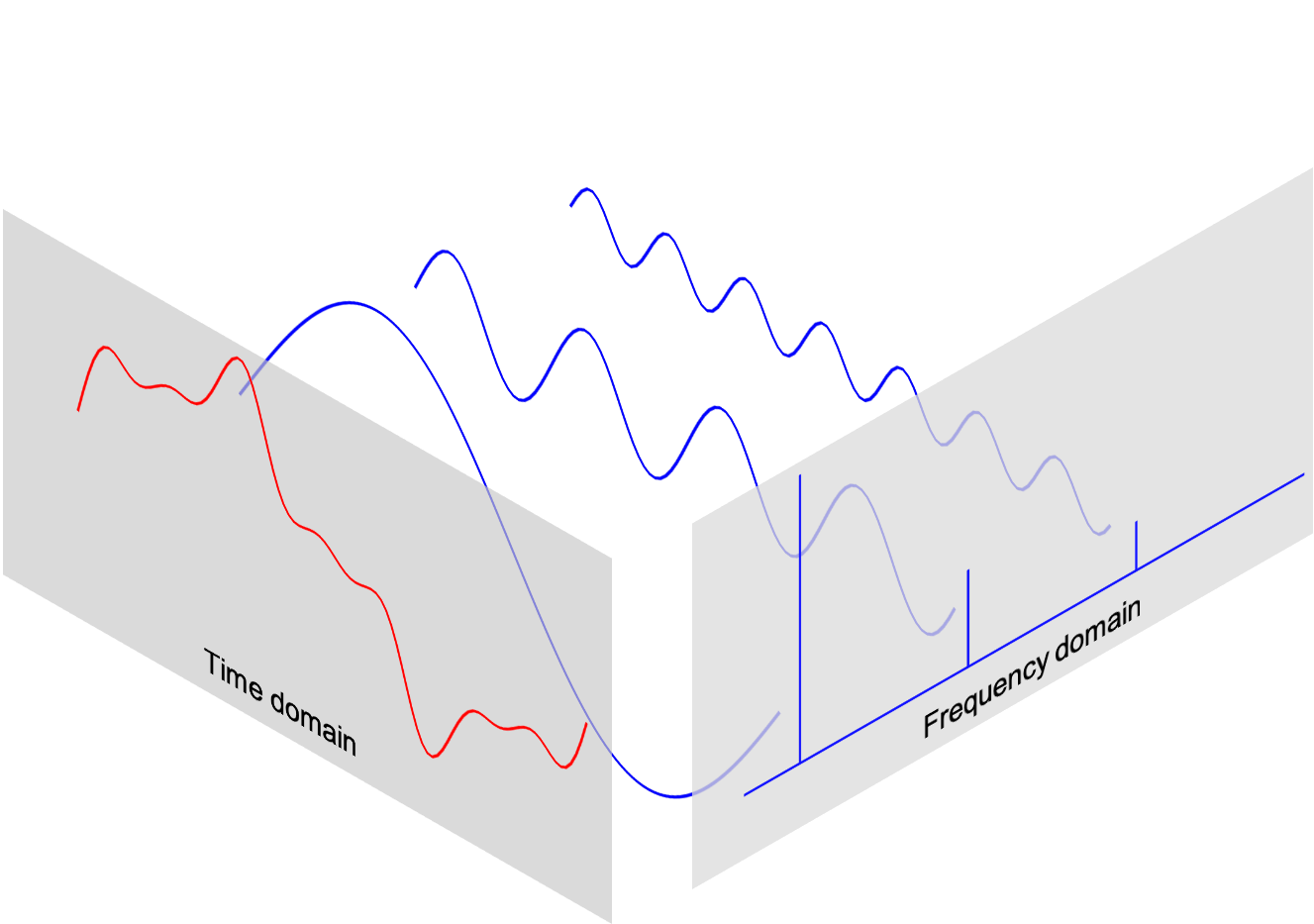

There are more complicated cases in the real world; it would be great if we have a method that we can use to analyze the characteristics of the wave. The Fourier Transform can be used for this purpose, which decomposes any signal into a sum of simple sine and cosine waves that we can easily measure the frequency, amplitude, and phase. The Fourier transform can be applied to continuous or discrete waves, in this chapter, we will only talk about the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT).

Using the DFT, we can compose the above signal to a series of sinusoids, each with a different frequency. The following 3D figure shows the idea behind the DFT: the above signal results from the sum of 3 different sine waves. The time domain signal, which is the above signal we saw, can be transformed into a figure in the frequency domain called the DFT amplitude spectrum, where the signal frequencies are shown as vertical bars. The height of the bar after normalization is the signal's amplitude in the time domain. You can see that the three vertical bars correspond to the three frequencies of the sine wave, which are also plotted in the figure.

In this section, we will learn how to use DFT to compute and plot the DFT amplitude spectrum.

DFT¶

The DFT can transform a sequence of evenly spaced signal to the information about the frequency of all the sine waves that needed to sum to the time domain signal. It is defined as:

$$ X_k = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}{x_n\cdot e^{-i2\pi{kn/N}}} = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}{x_n[cos(2\pi{kn/N}) -i\cdot sin(2\pi{kn/N})]}$$

where

- N = number of samples

- n = current sample

- k = current frequency, where $ k\in [0,N-1]$

- $x_n$ = the sine value at sample n

- $X_k$ = The DFT which include information of both amplitude and phase

Also, the last expression in the above equation derived from the Euler's formula, which links the trigonometric functions to the complex exponential function: $e^{i\cdot x} = cosx+i\cdot sinx$

Due to the nature of the transform, $X_0 = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}x_n$. If $N$ is an odd number, the elements $X_1, X_2, ..., X_{(N-1)/2}$ contain the positive frequency terms, and the elements $X_{(N+1)/2}, ..., X_{N-1}$ contain the negative frequency terms, in order of decreasingly negative frequency. While if $N$ is even, the elements $X_1, X_2, ..., X_{N/2-1}$ contain the positive frequency terms, and the elements $X_{N/2},...,X_{N-1}$ contain the negative frequency terms, in order of decreasingly negative frequency. If our input signal $x$ is a real-valued sequence, the DFT output $X_n$ for positive frequencies is the conjugate of the values $X_n$ for negative frequencies, and the spectrum will be symmetric. Therefore, usually, we only plot the DFT corresponding to the positive frequencies.

Note that the $X_k$ is a complex number that encodes both the amplitude and phase information of a complex sinusoidal component $e^{i\cdot 2\pi kn/N}$ of function $x_n$. The amplitude and phase of the signal can be calculated as:

$$amp = \frac{|X_k|}{N}= \frac{\sqrt{Re(X_k)^2 + Im(X_k)^2}}{N}$$ $$phase = atan2(Im(X_k), Re(X_k))$$

where $Im(X_k)$ and $Re(X_k)$ are the imagery and real part of the complex number, $atan2$ is the two-argument form of the $arctan$ function.

The amplitudes returned by DFT are equal to the amplitudes of the signals fed into the DFT if we normalize it by the number of sample points. Note that doing this will divide the power between the positive and negative sides. If the input signal is real-valued sequence as we described above, the spectrum of the positive and negative frequencies will be symmetric, therefore, we will only look at one side of the DFT result, and instead of divide $N$, we divide $N/2$ to get the amplitude corresponding to the time domain signal.

Now that we have the basic knowledge of DFT, let's see how we can use it.

Example¶

Generate 3 sine waves with frequencies 1 Hz, 4 Hz, and 7 Hz, amplitudes 3, 1 and 0.5, and phase all zeros. Add this 3 sine waves together with a sampling rate 100 Hz, you will see that it is the same signal we just showed.

plot_complex()

Example¶

Write a function DFT(x) which takes in one argument, x - input 1 dimensional real-valued signal. The function will calculate the DFT of the signal and return the DFT values. Apply this function to the signal we generated above and plot the result.

def DFT(x):

'''

Function to calculate the

discrete Fourier Transform

of a 1D real-valued signal x

'''

N = len(x)

n = np.arange(N)

k = n.reshape((N, 1))

e = np.exp(-2j * np.pi * k * n / N)

X = np.dot(e, x)

return X

X = DFT(x)

# calculate the frequency

N = len(X)

n = np.arange(N)

T = N/sr

freq = n/T

plt.figure(figsize = (8, 6))

plt.stem(freq, abs(X), 'b', markerfmt=" ", basefmt="-b")

plt.xlabel('Freq (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('DFT Amplitude |X(freq)|')

plt.show()

We can see from here that the output of the DFT is symmetric at half of the sampling rate (you can try different sampling rate to test). This half of the sampling rate is called Nyquist frequency or the folding frequency, it is named after the electronic engineer Harry Nyquist. He and Claude Shannon have the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, which states that a signal sampled at a rate can be fully reconstructed if it contains only frequency components below half that sampling frequency, thus the highest frequency output from the DFT is half the sampling rate.

plot_fft()

We can see by plotting the first half of the DFT results, we can see 3 clear peaks at frequency 1 Hz, 4 Hz, and 7 Hz, with amplitude 3, 1, 0.5 as expected. This is how we can use the DFT to analyze an arbitrary signal by decomposing it to simple sine waves.

The inverse DFT¶

Of course, we can do the inverse transform of the DFT easily.

$$ x_n = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=0}^{N-1}{X_k\cdot e^{i\cdot 2\pi{kn/N}}}$$

We will leave this as an exercise for you to write a function.

The limit of DFT¶

The main issue with the above DFT implementation is that it is not efficient if we have a signal with many data points. It may take a long time to compute the DFT if the signal is large.

Example¶

Write a function to generate a simple signal with different sampling rate, and see the difference of computing time by varying the sampling rate.

def gen_sig(sr):

'''

function to generate

a simple 1D signal with

different sampling rate

'''

ts = 1.0/sr

t = np.arange(0,1,ts)

freq = 1.

x = 3*np.sin(2*np.pi*freq*t)

return x

# sampling rate =2000

sr = 2000

%timeit DFT(gen_sig(sr))

88.3 ms ± 7.56 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)

# sampling rate 20000

sr = 20000

%timeit DFT(gen_sig(sr))

7.13 s ± 289 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

We can see that, with the number of data points increasing, we can use a lot of computation time with this DFT. Luckily, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was popularized by Cooley and Tukey in their 1965 paper that solve this problem efficiently, which we will look at next.

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)¶

The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is an efficient algorithm to calculate the DFT of a sequence. It is described first in Cooley and Tukey's classic paper in 1965, but the idea can be traced back to Gauss's unpublished work in 1805. A divide-and-conquer algorithm recursively breaks the DFT into smaller DFTs to bring down the computation. As a result, it successfully reduces the complexity of the DFT from $O(n^2)$ to $O(nlogn)$, where $n$ is the size of the data. This reduction in computation time is significant, especially for data with large $N$, therefore making FFT widely used in engineering, science, and mathematics. The FFT algorithm is the Top 10 algorithm of 20th century by the journal Computing in Science & Engineering.

Let's introduce to you how the FFT reduces the computation time. The content of this section is heavily based on this great tutorial put together by Jake VanderPlas.

Symmetries in the DFT¶

The answer to how FFT speedup the computing of DFT lies in the exploitation of the symmetries in the DFT. Let's take a look of the symmetries in the DFT. From the definition of the DFT equation

$$X_k = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}{x_n\cdot e^{-i2\pi{kn/N}}}$$

we can calculate the

$$X_{k+N} = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}{x_n\cdot e^{-i2\pi{(k+N)n/N}}} = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}{x_n\cdot e^{-i2\pi{n}}\cdot e^{-i2\pi{kn/N}}}$$

Note that, $e^{-i2\pi{n}} = 1$, therefore, we have

$$X_{k+N} = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}{x_n\cdot e^{-i2\pi{kn/N}}} = X_k$$

with a little extension, we can have

$$X_{k+i\cdot N} = X_k, \text{ for any integer i}$$

This means that within the DFT, we clearly have some symmetries that we can use to reduce the computation.

Tricks in FFT¶

Since we know there are symmetries in the DFT, we can consider to use it reduce the computation, because if we need to calculate both $X_k$ and $X_{k+N}$, we only need to do this once. This is exactly the idea behind the FFT. Cooley and Tukey showed that we can calculate DFT more efficiently if we continue to divide the problem into smaller ones. Let's first divide the whole series into two parts, i.e. the even number part and the odd number part:

\begin{eqnarray*} X_{k} &=& \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}{x_n\cdot e^{-i2\pi{kn/N}}} \\ &=& \sum_{m=0}^{N/2-1}{x_{2m}\cdot e^{-i2\pi{k(2m)/N}}} + \sum_{m=0}^{N/2-1}{x_{2m+1}\cdot e^{-i2\pi{k(2m+1)/N}}} \\ &=& \sum_{m=0}^{N/2-1}{x_{2m}\cdot e^{-i2\pi{km/(N/2)}}} + e^{-i2\pi{k/N}}\sum_{m=0}^{N/2-1}{x_{2m+1}\cdot e^{-i2\pi{km/(N/2)}}} \end{eqnarray*}

We can see that the two more minor terms, which only have half of the size ($\ \frac {N}{2}$) in the above equation, are two smaller DFTs. For each term, the $ 0\leq m \le \frac{N}{2}$, but $ 0\leq k \le N$, therefore, we can see that half of the values will be the same due to the symmetry properties we described above. Thus, we only need to calculate half of the fields in each term. Of course, we don't need to stop here, we can continue to divide each term into half with the even and odd values until it reaches the last two numbers, then calculation will be really simple.

This is how FFT works using this recursive approach. Let's see a quick and dirty implementation of the FFT. Note that the input signal to FFT should have a length of power of 2. If the length is not, usually we need to fill up zeros to the next power of 2 size.

def FFT(x):

'''

A recursive implementation of

the 1D Cooley-Tukey FFT, the

input should have a length of

power of 2.

'''

N = len(x)

if N == 1:

return x

else:

X_even = FFT(x[::2])

X_odd = FFT(x[1::2])

factor = \

np.exp(-2j*np.pi*np.arange(N)/ N)

X = np.concatenate(\

[X_even+factor[:int(N/2)]*X_odd,

X_even+factor[int(N/2):]*X_odd])

return X

# sampling rate

sr = 128

# sampling interval

ts = 1.0/sr

t = np.arange(0,1,ts)

freq = 1.

x = 3*np.sin(2*np.pi*freq*t)

freq = 4

x += np.sin(2*np.pi*freq*t)

freq = 7

x += 0.5* np.sin(2*np.pi*freq*t)

plt.figure(figsize = (8, 6))

plt.plot(t, x, 'r')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.show()

🚀 In class¶

Use the FFT function to calculate the Fourier transform of the above signal. Plot the amplitude spectrum for both the two-sided and one-side frequencies.

X=FFT(x)

# calculate the frequency

N = len(X)

n = np.arange(N)

T = N/sr

freq = n/T

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 6))

plt.subplot(121)

plt.stem(freq, abs(X), 'b', \

markerfmt=" ", basefmt="-b")

plt.xlabel('Freq (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('FFT Amplitude |X(freq)|')

# Get the one-sided specturm

n_oneside = N//2

# get the one side frequency

f_oneside = freq[:n_oneside]

# normalize the amplitude

X_oneside =X[:n_oneside]/n_oneside

plt.subplot(122)

plt.stem(f_oneside, abs(X_oneside), 'b', \

markerfmt=" ", basefmt="-b")

plt.xlabel('Freq (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('Normalized FFT Amplitude |X(freq)|')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Example¶

Generate a simple signal for length 2048, and time how long it will run the FFT and compare the speed with the DFT.

def gen_sig(sr):

'''

function to generate

a simple 1D signal with

different sampling rate

'''

ts = 1.0/sr

t = np.arange(0,1,ts)

freq = 1.

x = 3*np.sin(2*np.pi*freq*t)

return x

# sampling rate =2048

sr = 2048

%timeit FFT(gen_sig(sr))

10.4 ms ± 27.2 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each)

We can see that, for a signal with length 2048 (about 2000), this implementation of FFT uses 16.9 ms instead of 120 ms using DFT. Note that, there are also a lot of ways to optimize the FFT implementation which will make it faster. In the next section, we will take a look of the Python built-in FFT functions, which will be much faster.

FFT in Python¶

In Python, there are very mature FFT functions both in numpy and scipy. In this section, we will take a look of both packages and see how we can easily use them in our work. Let's first generate the signal as before.

Example: FFT in Numpy¶

Use fft and ifft function from numpy to calculate the FFT amplitude spectrum and inverse FFT to obtain the original signal. Plot both results. Time the fft function using this 2000 length signal.

from numpy.fft import fft, ifft

X = fft(x)

N = len(X)

n = np.arange(N)

T = N/sr

freq = n/T

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 6))

plt.subplot(121)

plt.stem(freq, np.abs(X), 'b', \

markerfmt=" ", basefmt="-b")

plt.xlabel('Freq (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('FFT Amplitude |X(freq)|')

plt.xlim(0, 10)

plt.subplot(122)

plt.plot(t, ifft(X), 'r')

plt.xlabel('Time (s)')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

/Users/matgyver/anaconda3/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1699: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part return math.isfinite(val) /Users/matgyver/anaconda3/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1345: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part return np.asarray(x, float)

%timeit fft(x)

11.7 µs ± 47.2 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100,000 loops each)

Example: FFT in Scipy¶

Use fft and ifft function from scipy to calculate the FFT amplitude spectrum and inverse FFT to obtain the original signal. Plot both results. Time the fft function using this 2000 length signal.

from scipy.fftpack import fft, ifft

X = fft(x)

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 6))

plt.subplot(121)

plt.stem(freq, np.abs(X), 'b', \

markerfmt=" ", basefmt="-b")

plt.xlabel('Freq (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('FFT Amplitude |X(freq)|')

plt.xlim(0, 10)

plt.subplot(122)

plt.plot(t, ifft(X), 'r')

plt.xlabel('Time (s)')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

/Users/matgyver/anaconda3/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1699: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part return math.isfinite(val) /Users/matgyver/anaconda3/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1345: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part return np.asarray(x, float)

%timeit fft(x)

Now we can see that the built-in fft functions are much faster and easy to use, especially for the scipy version. Here is the results for comparison (running on my Macbook M1 Max pro, YMMV):

- Implemented DFT: ~80 ms

- Implemented FFT: ~10 ms

- Numpy FFT: ~11 µs

- Scipy FFT: ~10 µs

More examples¶

Let us see some more examples how to use FFT in real-world applications.

Electricity demand in the Midwest¶

First, we will explore the electricity demand from the midwest grid from 2023-10-26 to 2023-11-02. You can download data from U.S. Energy Information Administration. Here, I have already downloaded the data, therefore, we will use it directly.

The electricity demand data from the Midwest is stored in '930-data-export.csv' in 3 columns. Remember we learned how to read CSV file using numpy. Here, we will use another package - pandas, which is a very popular package to deal with time series data. We will not teach you this package here, as an exercise, you should learn how to use it by yourself. Let us read in the data first.

The read_csv function will read in the CSV file. Pay attention to the parse_dates parameter, which will find the date and time in column one. The data will be read into a pandas DataFrame, we use df to store it. Then we will change the header in the original file to something easier to use.

# define a 'real' time zone for each abbreviation:

df = pd.read_csv('./data/930-data-export.csv',delimiter=',')

df['Timestamp (Hour Ending)'] = df['Timestamp (Hour Ending)'].str.replace('EST|EDT', '', regex=True)

df['Timestamp (Hour Ending)'] = pd.to_datetime(df['Timestamp (Hour Ending)'],format='mixed').dt.tz_localize('US/Eastern')

df.rename(columns={'Timestamp (Hour Ending)':'hour',

'Total Midwest Demand (MWh)':'demand'},inplace=True)

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 6))

plt.plot(df['hour'], df['MISO Demand (MWh)'])

plt.xlabel('Datetime')

plt.ylabel('Total Midwest Demand (MWh)')

plt.xticks(rotation=25)

plt.show()

From the plotted time series, it is hard to tell there are some patterns behind the data. Let us transform the data into frequency domain and see if there is anything interesting.

X = fft(df['MISO Demand (MWh)'])

N = len(X)

n = np.arange(N)

# get the sampling rate

sr = 1 / (60*60)

T = N/sr

freq = n/T

# Get the one-sided specturm

n_oneside = N//2

# get the one side frequency

f_oneside = freq[:n_oneside]

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 6))

plt.plot(f_oneside, np.abs(X[:n_oneside]), 'b')

plt.xlabel('Freq (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('FFT Amplitude |X(freq)|')

plt.show()

We see some clear peaks in the FFT amplitude figure, but it is hard to tell what are they in terms of frequency. Let us plot the results using hours and highlight some of the hours associated with the peaks.

# convert frequency to hour

t_h = 1/f_oneside / (60 * 60)

plt.figure(figsize=(12,6))

plt.plot(t_h, np.abs(X[:n_oneside])/n_oneside)

plt.xticks([12, 24, 84, 168])

plt.xlim(0, 200)

plt.xlabel('Period ($hour$)')

plt.show()

/var/folders/rq/kct3v3md3x79drbqvbswb6wc0000gn/T/ipykernel_82722/1034189290.py:2: RuntimeWarning: divide by zero encountered in divide t_h = 1/f_oneside / (60 * 60)

We can now see some interesting patterns, i.e. three peaks associate with 12 and 24 hours. These peaks mean that we see some repeating signal every 12 and 24 hours. This makes sense and corresponding to our human activity pattern. The FFT can help us to understand some of the repeating signal in our physical world.

Filtering a signal using FFT¶

Filtering is a process in signal processing to remove some unwanted part of the signal within certain frequency range. There are low-pass filter, which tries to remove all the signal above certain cut-off frequency, and high-pass filter, which does the opposite. Combining low-pass and high-pass filter, we will have bandpass filter, which means we only keep the signals within a pair of frequencies. Using FFT, we can easily do this. Let us play with the following example to illustrate the basics of a band-pass filter. Note: we just want to show the idea of filtering using very basic operations, in reality, the filtering process are much more sophisticated.

Example¶

We can use the signal we generated at the beginning of this section (the mixed sine waves with 1, 4, and 7 Hz), and high-pass filter this signal at 6 Hz. Plot the filtered signal and the FFT amplitude before and after the filtering.

# FFT the signal

sig_fft = fft(x)

# copy the FFT results

sig_fft_filtered = sig_fft.copy()

# obtain the frequencies using scipy function

freq = fftfreq(len(x), d=1./2000)

# define the cut-off frequency

cut_off = 6

# high-pass filter by assign zeros to the

# FFT amplitudes where the absolute

# frequencies smaller than the cut-off

sig_fft_filtered[np.abs(freq) < cut_off] = 0

# get the filtered signal in time domain

filtered = ifft(sig_fft_filtered)

# plot the filtered signal

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 6))

plt.plot(t, filtered)

plt.xlabel('Time (s)')

plt.ylabel('Amplitude')

plt.show()

# plot the FFT amplitude before and after

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 6))

plt.subplot(121)

plt.stem(freq, np.abs(sig_fft), 'b', \

markerfmt=" ", basefmt="-b")

plt.title('Before filtering')

plt.xlim(0, 10)

plt.xlabel('Frequency (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('FFT Amplitude')

plt.subplot(122)

plt.stem(freq, np.abs(sig_fft_filtered), 'b', \

markerfmt=" ", basefmt="-b")

plt.title('After filtering')

plt.xlim(0, 10)

plt.xlabel('Frequency (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('FFT Amplitude')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

/Users/matgyver/anaconda3/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1699: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part return math.isfinite(val) /Users/matgyver/anaconda3/lib/python3.11/site-packages/matplotlib/cbook.py:1345: ComplexWarning: Casting complex values to real discards the imaginary part return np.asarray(x, float)

From the above example, by assigning any absolute frequencies' FFT amplitude to zero, and returning back to time domain signal, we achieve a very basic high-pass filter in a few steps. You can try to implement a simple low-pass or bandpass filter by yourself. Therefore, FFT can help us get the signal we are interested in and remove the ones that are unwanted.

There are also many amazing applications using FFT in science and engineering and we will leave you to explore by yourself.